| Media Type: |

|

| Art Type: |

Other |

| Artists: |

None Specified

|

Neil Gaiman is a huge fan

AT THE TURN OF THE 1980S, IF YOU WANTED TO READ COMICS, YOU WERE PRETTY MUCH CONFINED TO SPIDER-MAN, SUPERMAN AND THEIR SPANDEXED STABLEMATES AT MARVEL AND DC. THE UNDERGROUND COMIC SCENE OF THE 60S AND 70S HAD FADED ALONGSIDE ART SPIEGELMAN AND ROBERT CRUMB, AND POSTPUNK INDEPENDENTS SUCH AS DAVE SIM’S CEREBUS THE AARDVARK HAD YET TO FULLY TAKE UP THE SLACK. THEN, IN 1981, ALONG CAME LOVE AND ROCKETS, A CRUDELY PRINTED, SELF-PUBLISHED COMIC FROM THREE CALIFORNIA BROTHERS, JAIME, GILBERT AND MARIO, KNOWN AS LOS BROS HERNANDEZ. IT WAS – AND REMAINS – ONE OF THE MOST ORIGINAL AND INFLUENTIAL COMIC PROJECTS EVER.

“I was an enormous fan,” says Neil Gaiman, the multi-award-winning author and graphic novelist. “I still am. I don’t really understand why the material of Love and Rockets isn’t widely regarded as one of the finest pieces of fiction of the last 35 years. Because it is.”

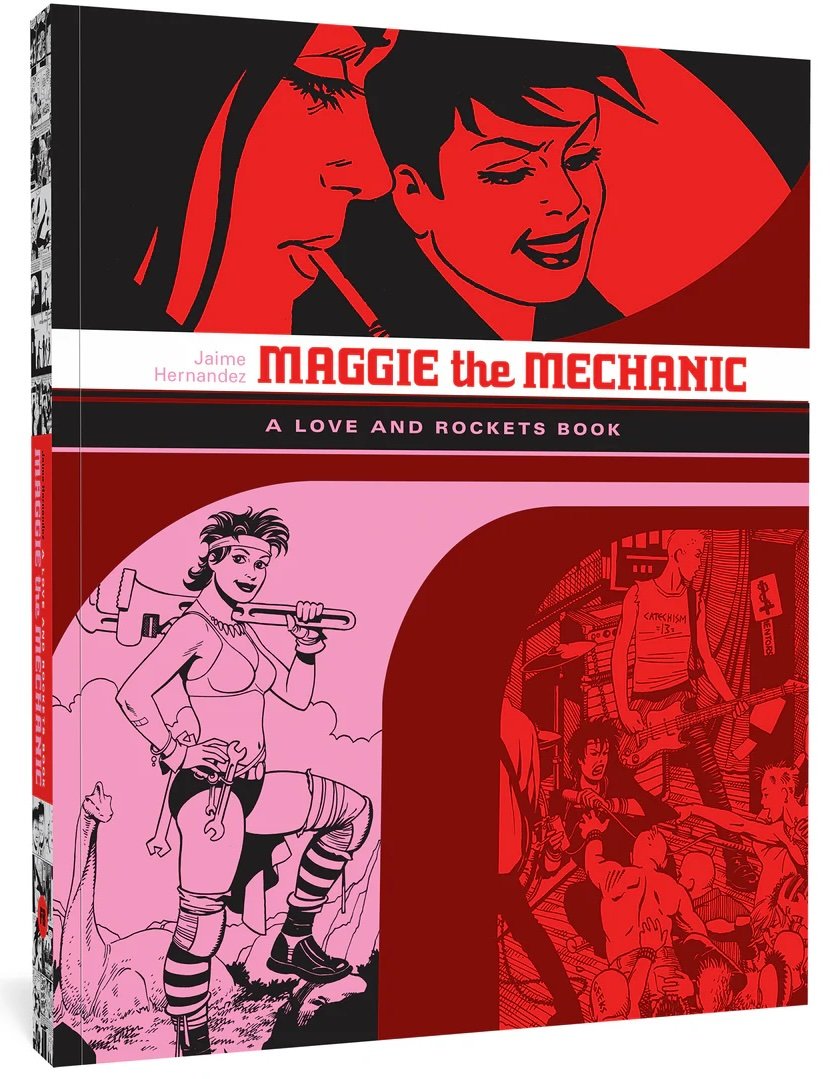

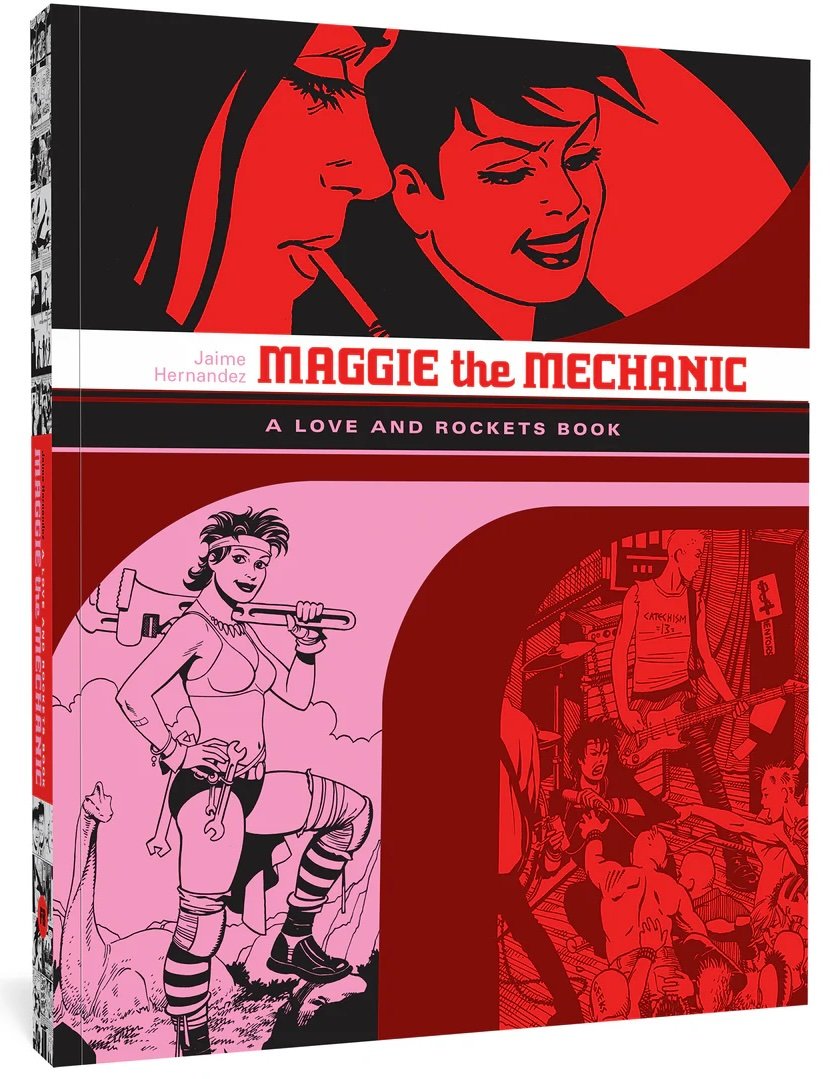

Although the magazine was filled with one-off and semi-regular strips, the heart of Love and Rockets is two ongoing series: Jaime’s Locas and Gilbert’s Heartbreak Soup. The latter is an epic story of life in the fictional Mexican town of Palomar – soap-operatic telenovela meets the magical realism of Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. And that’s barely even beginning to do it justice. Locas is even harder to describe. It morphed from the tale of Maggie, a young “prosolar mechanic”, replete with rocket ships and dinosaurs, into the slice-of-life story of young people in a California town called Hoppers, with the odd lady wrestler and pneumatic superhero thrown in.

It’s true the casts of both stories are immense. Locas is, at its heart, the love story of Maggie and Hopey and the almost innumerable characters who pass through their lives, from Maggie’s on-off boyfriend Ray to witchy Izzy to blond bombshell Penny Century to the inexplicably horned billionaire HR Costigan. The roll call in Heartbreak Soup is just as vast: narrative linchpin and Palomar’s mayor Luba; a Pedro Almodóvar-esque leading lady with – and this can’t be avoided – enormous breasts; multitasking midwife-cum-sheriff Chelo; vain Pipo; the enigmatic Errata Stigmata …

In their first editorial, the brothers wrote: “We, the brothers (Jaime, ’Bert, and Mario) Hernandez, have tried to get into the comics jungle for a few years now, but could never seem to make the right connections. But now editor (and future contributor) Mario decided that it was time to do it ourselves. Our own comics with our own ideas; our own mistakes and our own accomplishments.”

Without Love and Rockets, it's unlikely DC would have ventured into edgier fare such as Watchmen

That first issue, hawked around conventions for a dollar a copy, was brought to the attention of Gary Groth at indie comics publishing house Fantagraphics. By the following year, 1982, Love and Rockets was professionally published. It ran to 50 magazine-size issues, ending in 1996. From 2001 to 2007, it re-emerged in standard comic-book format, and since 2008 it has been published as an annual 104-page album. Unlike mainstream comics, where universes are endlessly rebooted and reset to keep the superheroes eternally youthful, the Hernandez brothers have allowed their characters to age along with the readership, which forms part of its enduring appeal.

As does diversity – especially the portrayal of women. “I grew up on a very, very remote farm in an incredibly white part of the Oregon coast,” remembers comic writer Gail Simone. “As a kid, the first issue of Love and Rockets I saw astonished me not just with its visual and storytelling mastery, but with the worlds it focused on – characters of every shape and background, from women selling babosas barefooted to sexy, smart mechanic girlfriends. I’d never experienced anything like it, and that’s because there is nothing else like it.”

REF

|

|